““The best geologist is the one that has seen the most rocks””

World Class and Spectacular Late Cambrian Microbial Reef Outcrops in Mason County, Texas

October 11-13, 2019

Photos from Christian Dohse unless otherwise noted.

Big Bend Ranch State Park

February 25-27, 2019

Summary pending…

All photos from Christian Dohse.

Albian Rudist buildup

November 18, 2017

Many thanks to Charlotte Sullivan for a really interesting and well-planned field trip on Nov. 18th. Thirty-six members of the Society examined fascinating exposures of the lower part of the Edwards group in the spillway of the Lake Georgetown dam in beautiful weather. We saw three types of rudistid mounds as well as a channel or two, laminated sediments, at least two types of diagenetic concretions, calcite bedding-plane (jack-up?) veins, microbial mats (stromatolites), some of which showed current flow to the west, and evidence for dolomitisation and dedolomitisation. There were apparent soft-sediment deformation features, at least two of which also suggested westerly-directed shear. All in all a great day: thank you Charlotte!"

Guidebook available here.

Description, photos, and captions from John Berry.

Less Frequented Springs of the Austin Area

February 25, 2017

On Saturday, February 25th, AGS had a fieldtrip led by Al Cherepon, Scott Hiers and Sylvia Pope to springs that are not typically on the tourist, or geologist, route. This fieldtrip took AGS members to lesser known springs in the Austin area, starting in the Great Hills/Arboretum area and ending at a spectacular hidden spring near the Colorado River. Although we only visited six springs during the fieldtrip, hundreds more occur throughout the greater Austin area at recognized geologic horizons. The six stops provided an opportunity to observe groundwater discharge from the Walnut Formation (Fm.), the northern Edwards, the upper Glen Rose, the Buda/Del Rio contact, the Austin Chalk and Quaternary Colorado River terrace deposits. Fault or fracture control was observed at Stop 1, Hearth/Great Hills Spring. Characteristics such as hydrophytic vegetation and tufa deposits occur at virtually all of the springs. Unique ecological characteristics at Stop 3, Little Stillhouse Hollow Spring, provide an inside view of the Edwards Aquifer from inside a rock shelter and habitat for the Jollyville Plateau salamander. Several stops also have notable historical significance, as springs were a crucial resource during the early settlement of the area. McKinney built a grist mill in 1849 at Stop 6, Costley Spring. The terraced tufa deposits, waterfall cascading from an upstream dam and the spectacular exposure of the terrace deposits atop the Taylor Group made the last stop of the day, in many opinions, the best stop of the day.

--Sylvia Pope

Mini-field trip: Visit to Gault Archeological Site

November 19, 2016

On Sat. Nov. 19th we had a very successful Mini Field Trip to the Gault archaeological site north of Florence. Three and a half million artifacts were excavated there, including several hundred from pre-Clovis times. The site also boasts the oldest rock art in the Americas and the floor of the oldest house in North America. We had 31 members and friends in attendance, and the weather was perfect. The Executive Director of the Gault School of Archaeology, D. Clark Wernecke, gave us a very interesting and enlightening three hour tour, during which he debunked, often on the basis of evidence from this site, many of the dogmas about the peopling of the Americas.

Dr. Wernecke explained that the chert found in the Edwards group was extremely valuable in ancient times and has been found in sites as far as 1500 miles away. At Gault most of the chert found in outcrops is not of the best quality, but is brittle (Fig.1). However, weathering and erosion act as a natural refining process, and the chert that survives to become boulders in the stream bed is of excellent quality for tool making. Evidence from Gault shows that tools were routinely reworked as they got broken or blunted, and that “arrowheads” were really spearpoints, as they were too heavy to make effective arrows. He discussed the effectiveness of handthrown weapons versus spears projected at high velocity by an atlatl (Fig.2) .

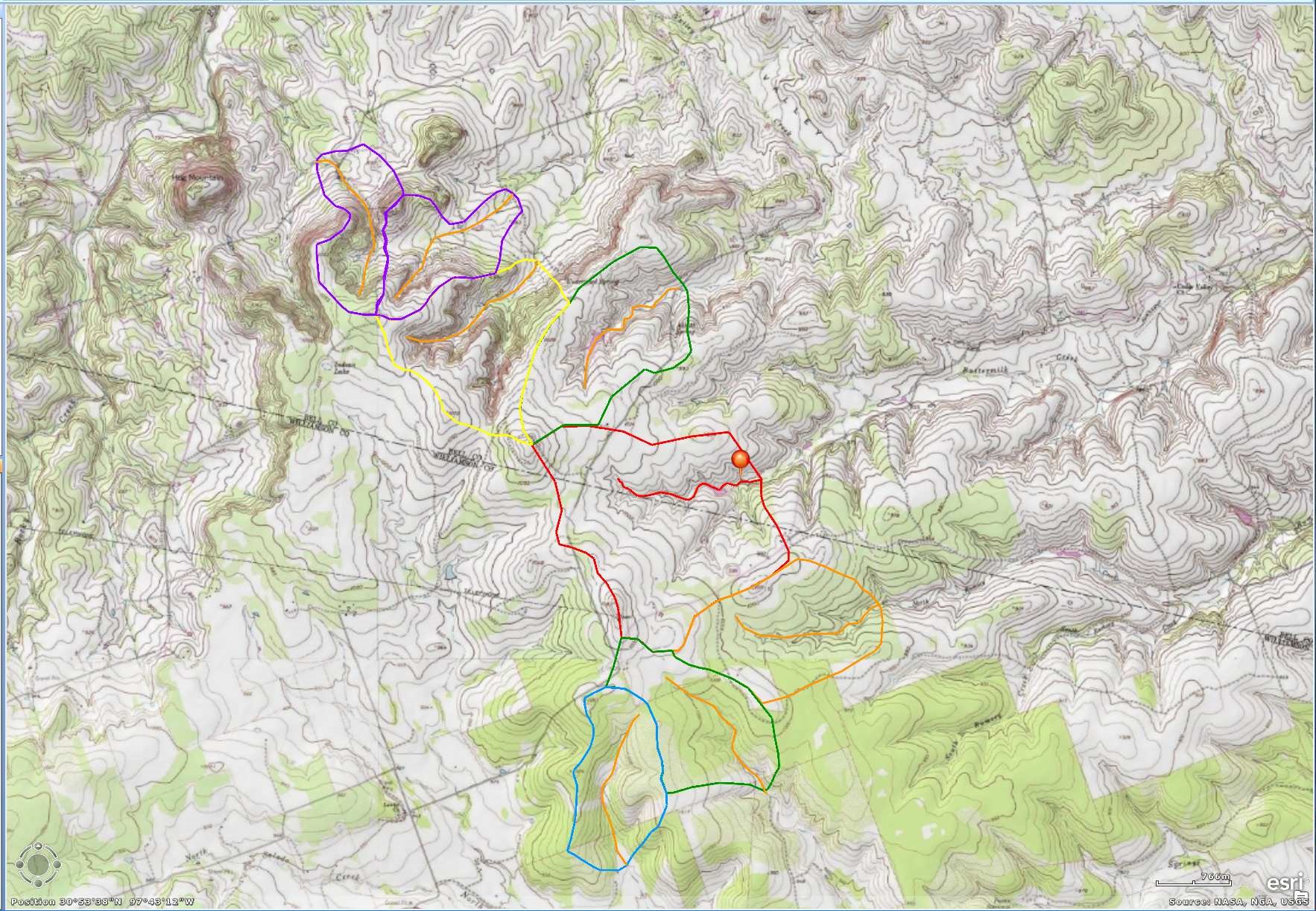

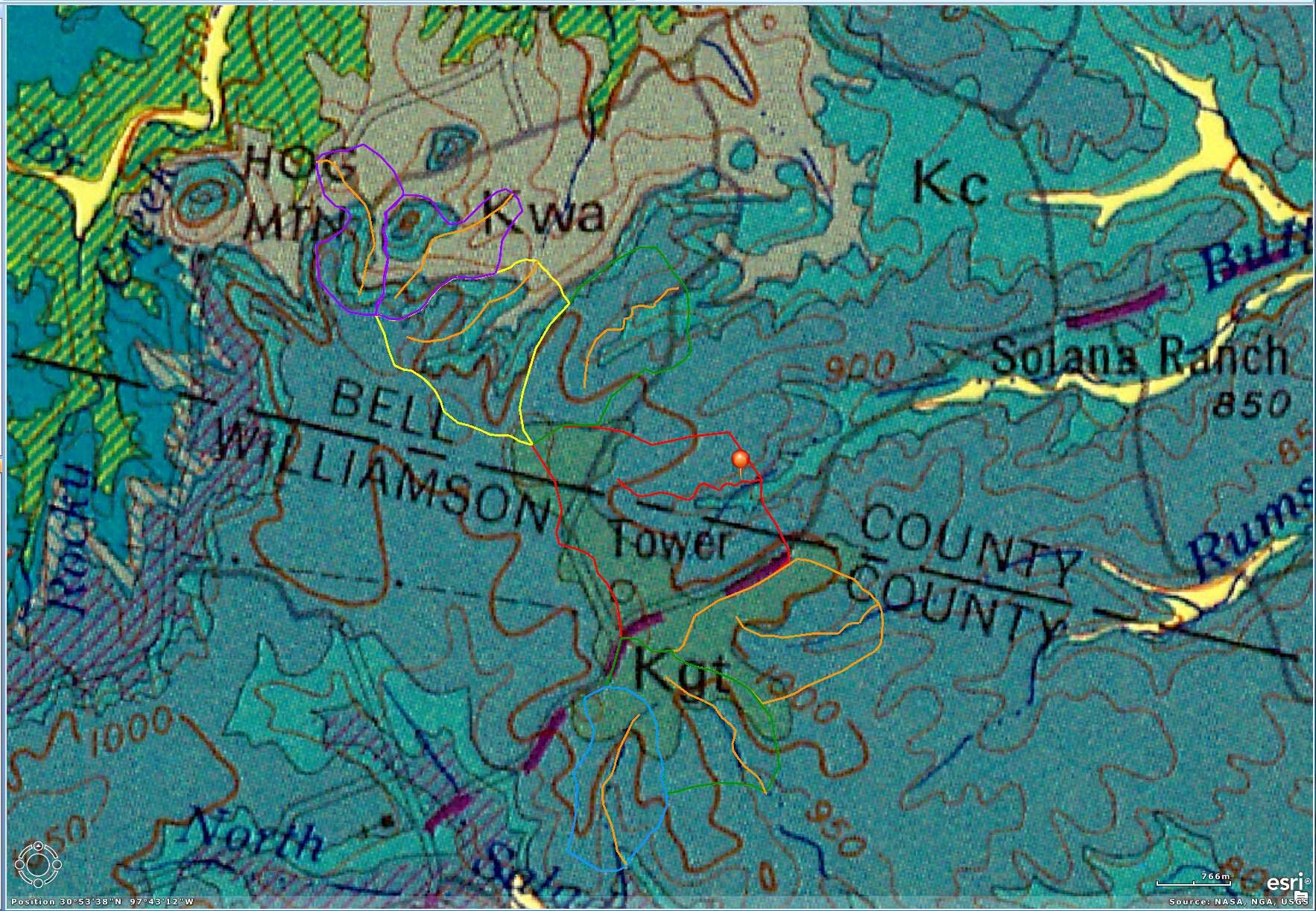

Dr. Wernecke explained that the site has been preserved because the alluvial sediments of the valley floor have not been scoured out by a flash flood in the last 15,000 years, whereas all the surrounding valleys have been scoured to bedrock within the last millennium or two (Fig.3). This fired me up to check the geological maps when I got home – the site is in the NW corner of the Austin AMS (2-degree) sheet.

The Gault site is 1.7km from the source of Buttermilk Creek. I traced on the map the watershed at Gault and those of six adjoining watersheds (Fig.4). It was immediately obvious that a much greater proportion of the Buttermilk Creek headwater area is underlain by the Georgetown limestone (Fig.5), and that the stream does not cut down to the base of the Edwards until the lower end of the Gault site: in fact, the “oldest house in North America” sits close to the Edwards-Comanche Peak contact and an area of poor drainage (marked by a patch of reeds), which probably marks the subcrop of the uppermost Comanche Peak. Adjacent creeks cut slot canyons well down into the relatively impervious Comanche Peak and Walnut formations, and are therefore more liable to scouring by flash floods. In contrast the headwater area of Buttermilk Creek is a surface of low relief. Thus rain falling onto the Buttermilk Creek headwaters infiltrates and soaks rather slowly through the marly Georgetown Lime, which covers 35% of the watershed as opposed to 0% to 15% of adjacent watersheds. This would lower the peak of the storm hydrograph in Buttermilk Creek versus neighboring drainages. Rain falling on the Edwards would infiltrate quickly, to issue from the ground at the downstream end of the archaeological site along the Comanche Peak contact, or perhaps even further downstream at the Walnut contact, as in the Austin area, thus reducing surface flow through the area of the site. In adjacent watersheds, where Comanche Peak and Walnut outcrop much closer to the source and in confined canyons, rapid transmission through the Edwards to the Comanche Peak aquitard would probably lead to a much more flashy regime in the part of the valley that is attractive to human settlement, and hence scouring out of any archaeological material.

Using this reasoning, only the two watersheds immediately south of Gault have a good chance of containing significant archaeological material, since they have very similar geology.

Core Workshop: Architectural variability and depositional trends in the Wilcox Group in Texas

October 20, 2016

The University of Texas at Austin and Bureau of Economic Geology (BEG) State of Texas Advanced Oil and Gas Resource Recovery (STARR) Program presented an all-day core workshop of the Wilcox Group in Texas. Following morning lectures on Wilcox sequence stratigraphy and depositional systems, a workshop was devoted to an afternoon’s to a review of cores in the Core Research Center (Building 131). Attendees got a hands-on view of key cores with a detailed review of depositional systems and reservoir facies. Workshop participants observed numerous examples of vertically superimposed sedimentary facies from fluvial, deltaic, and transgressive-shelf depositional systems.

Fall 2015

Austin Chalk Symposium: Core Workshop and Field Trip

AGS Guidebook 36

Karst and Recharge in the Barton Springs Segment of the Edwards Aquifer: Field Trip to the City of Austin’s Water Quality Protection Lands

April 11, 2016

Nico Hauwert and David Johns (AGS Guidebook 35)

Stops on this field trip illustrated the issues and controversy of upland recharge, geologic assessments of properties, karst-feature excavation, waste-water application over the recharge zone, and land acquisition. Participants visited several properties purchased specifically for water-quality and –quantity protection -- part of the Austin Water Quality Protection Lands program, where they observed outstanding natural karst features including a 120-foot-deep open shaft, large internal drainage basins, and whirl-pooling swallets. Results were presented from new research into recharge and groundwater flow, using evapotranspiration towers, dye tracing, and stream-flow gauging. Visits to ranches illustrated how trash disposal and water storage incorporated natural karst features, contrasted with present management of WQPL. Stops included a recently proposed wastewater effluent disposal site over the Edwards Aquifer, where discussion centered on the importance of hand-excavation in evaluating the significance of karst features.

Upper Cretaceous (Eagle Ford) Core Workshop

December 3, 2015

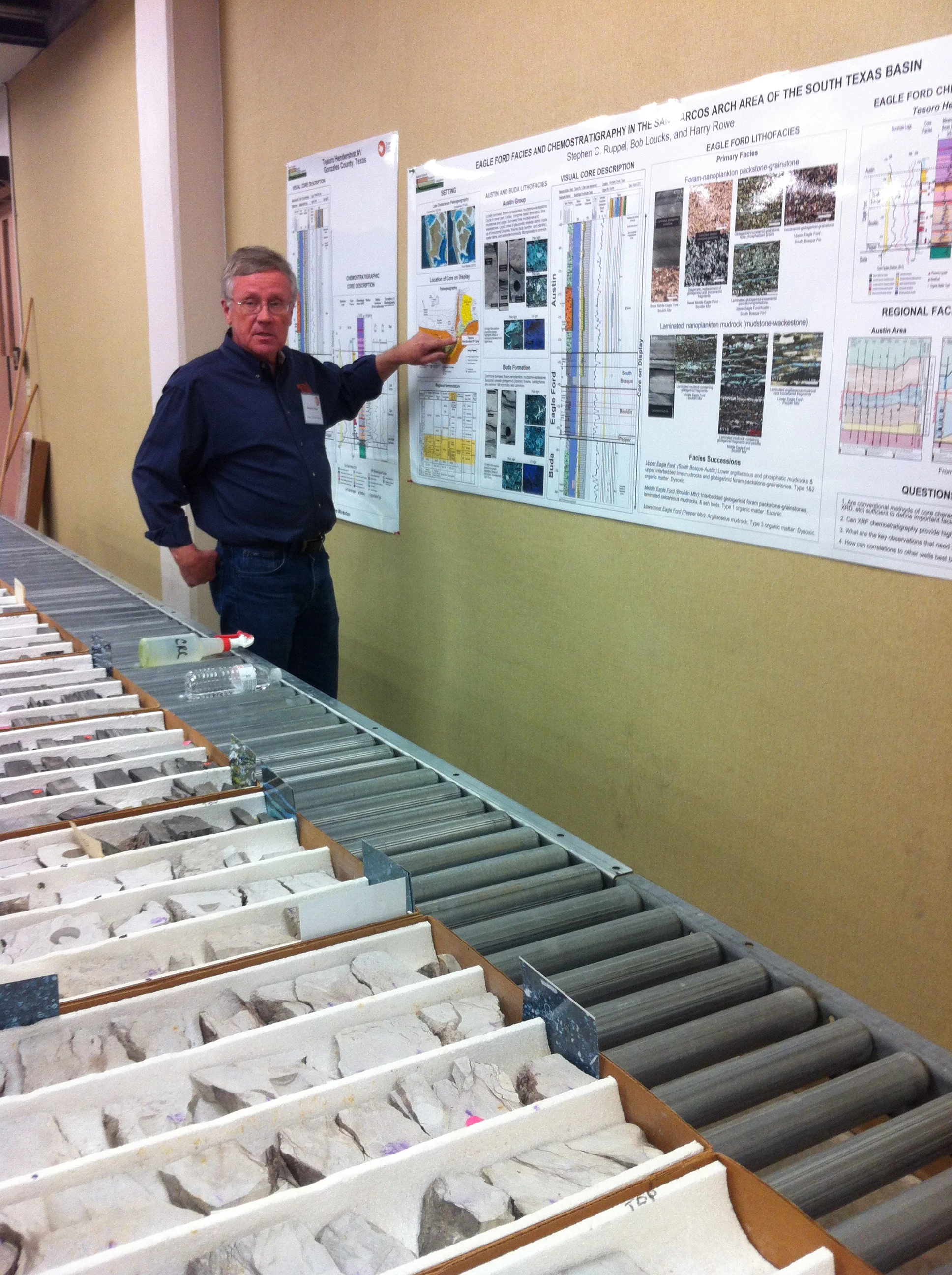

Bob Loucks, Steve Ruppel, Harry Rowe, Bill Ambrose, Greg Frebourg and Jiemin Lu

The Mudrock Systems Research Laboratory (MSRL) and the State of Texas Advanced Resource Recovery Project (STARR) of the University of Texas Bureau of Economic Geology presented a core workshop for a capacity crowd of 40 members of the Austin Geological Society on December 3rd. The workshop highlighted the Bureau’s extensive collection of well core including carbonates, shales, and sandstones. After a morning of introductory lectures accompanied by lively discussion, researchers presented 6 cores from the Upper Cretaceous of the South Texas-Louisiana Shelf and the Western Interior Seaway. Cores included such currently productive units as the Eagle Ford Shale, Niobrara Chalk, and the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale. Harry Rowe also demonstrated use of advanced core chemostratigraphy characterization equipment owned by the Bureau. An encore production of the workshop may be held in 2015 for the numerous AGS members who were unable to attend due to space limitations.

-- Robert M. Reed

December 13, 2014

Evaporite Karst, Edwards Group, Junction Texas area

Bob Loucks and Chris Zahm

The dissolution of a thick evaporite sequence is a large-scale post-depositional feature that affects thousands of square kilometers and produces intrastratal deformation within the interval of the former evaporite beds (meters to tens of meters, vertical) and suprastratal deformation, expressed by folds, faults (inverse and normal), and intense fracturing for tens to hundreds of feet above the collapsed evaporite beds. The Edwards limestone roadcuts along I-10, just east of Junction, Texas, provide excellent examples of evaporite collapse, where the Kirschberg evaporite was dissolved. We viewed the undeformed beds below, the breccias and fills within, and the abundant and spectacular structural deformation above the former evaporite section. This well-exposed evaporite system is an excellent analog for both hydrocarbon reservoirs and aquifers in carbonate rocks.

-- Bob Loucks